With one round to go, only one player, Semen Lomasov from Russia, is guaranteed the first place – he cannot be surpassed in the Open 14 category. A draw tomorrow will make Haik Martirosyan the Open 16 champion. The champions of other categories will be determined tomorrow. The struggle in the Girls championships will be particularly sharp – sudden losses of the leaders in all age groups ruined many plans.

Let us begin with them. Alexandra Obolentseva played the first nine days of the Under 18 championship perfectly – aggressively as White, accurately as Black. However, in the penultimate round, when the goal was so close, she suddenly collapsed…

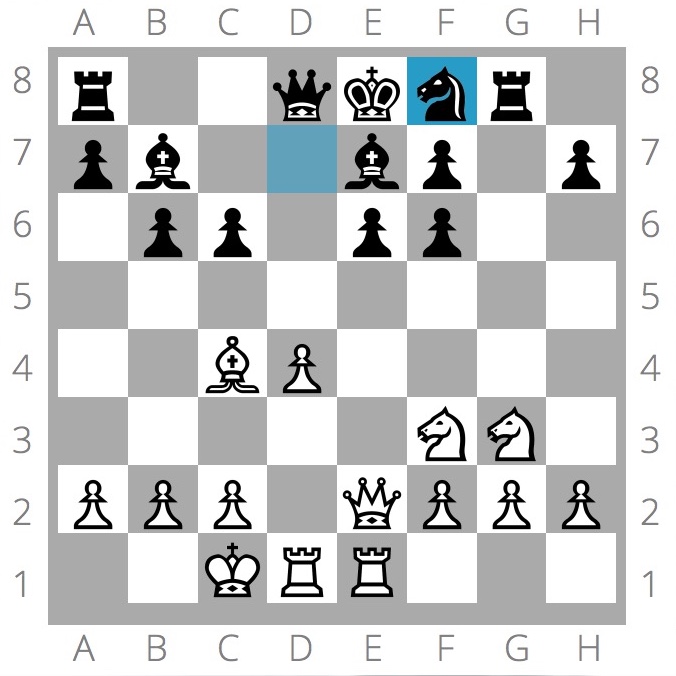

Normally Obolentseva senses dynamic opportunities of Black in the King’s Indian with her fingertips. Not today, though. The diagrammed position in the game against Uurtsaikh Uuriintuya from Mongolia (Black) is equal. The simplest way to prove it is 20…Bxc1 21.Qxc1 Kh8, and the attacks on opposite sides of the board must balance each other. However, the Mongolian wants more, and Alexandra accepts the challenge.

20…f4 21.Bd3?! (the bishop does not prevent e5-e4, and the g2-square becomes weak) 21…Qe7 22.Bc2?! (bringing the piece even further from the king) 22…Qg7 23.Nd2 Bd7! (aiming at the h3-pawn) 24.Qf3 Kh8 25.Bb2. Still not sensing any danger. White should have maintained the blockade by 25.Ne4 Bf5, and it is not easy to break through.

25…Be8! (hinting that a queen is a poor blocker) 26.Qe2? (more accurate is 26.Kh1, vacating the g1-square for a rook) 26…Rg8! 27.f3. If White is forced to play such move, she is definitely in trouble. On 27.Qf1 there is the elegant 27…Nxd5!, and 28.cxd5? fails to 28…Bb5!

27…Bd7?! (more accurate is 27…Nh5, combining the threats on g- and h-files) 28.Kh2? (the king is vulnerable here; after 28.Kh1 Nh5 29.Ne4 Bf5 30.Qd2 Qd7 31.Nf2 there is nothing forced for Black) 28…Qg3+ 29.Kh1 Rg5! 30.Rf1?! (better is 30.Qf1 and Re2) 30…Bxh3! A spectacular finale. White cannot survive under a coordinated attack of all Black’s pieces. Obolentseva resisted hopelessly until the 45th move, but the inevitable happened – her first loss in 10 games. She has 8 out of 10 now.

Her only rival Stavroula Tsolakidou won easily against Mahalakshmi, who got lost in a well-known variation of the French.

Black had no time to prepare a long castling and now gets punished for that. 13.d5! cxd5 (13…exd5? loses to 14.Nd4 Qd7 15.Bd3) 14.Bb5+ Nd7 15.Nd4 Kf8? Black has a difficult position after 15…a6 16.Bc6 Bxc6 17.Nxc6 Qc7 18.Nxe7 Kxe7 19.Rxd5, but at least it does not lose on the spot. The text leads to a quick finale.

16.Qh5! Rg7 (protecting on f7, but missing another hit) 17.Rxe6! Kg8 18.Rxe7 (all roads read to Rome by now) 18…Qxe7 19.Ngf5. Black resigns. The Greek moved on 8 out of 10.

The fate of the gold will be decided tomorrow. If Tsolakidou and Obolentseva tie for first, the Greek will likely become a champion, as she has a superior tie-break, and their individual game ended in a draw.

Shuvalova Polina (RUS)

Polina Shuvalova once again created problems for herself in the Girls 16 championship. Her opponent Mobina Alinasab got under time pressure and gave the Russian great winning chances. Alas, the Moscow champion did not use this opportunity. Actually, she even found the way to lose.

The knight transfer to f4 is called for. Black can also capture on a2, winning a pawn. Instead of that, Shuvalova blitzed out 31…Bxf5?! 32.exf5 Qd4 33.a3 Nbd5 34.Qd3 h5? This makes no sense. Black must trade queens are bring her king in the center with a clear advantage due to a better structure and piece activity.

35.Qxd4 exd4 36.Nc4 Nf4 37.Be4 b5 38.Nd2 Ned5? Preventing the bishop from going to b5. Fixating a weakness on h3 was necessary – 38…h4! And now White achieves a winning position, playing simple and natural moves. Black’s pawns on b5 and a6 are the deciding factor of the game.

39.gxh5! Kg7 40.Kg3 Nxh5+ 41.Kf3 Nhf4 42.Bxd5 Nxd5 43.Ke4! The tables have turned – the white king plays the key role, while the black king is a mere spectator. Shuvalova’s attempts to complicate things did not bring her anything.

Unfortunately for the hosts, Shuvalova’s rivals took the maximum out of her first loss – both Anna-Maja Kazarian and Hagawane Aakanksha won their games and surpassed the Russian. The Indian will also enjoy a tie-break advantage, as she defeated Kazarian in the round 5. Shuvalova can only hope for a miracle…

A complete shake up occurred in the Girls 14 championship. The Chinese Zhu Jiner, who started with 7.5 out of 8, began to crumble. Yesterday she lost to Olga Badelka from Belarus, and today suffered another defeat by Annie Wang from USA. The American slowly gathered small advantages and then suddenly threatened mate, for which there was no defense. Badelka also looked pale today, losing as White to Vantika Agrawal.

With one round to go, the Indian and the American have 8 out of 10. Wang is a bit closer to the gold thanks to a victory in their individual game, but who can really predict the events of the final round?

We will provide just two details about the Open championships. Maksim Vavulin, the leader of the Open 18 event, made another draw, and Manuel Petrosyan managed to catch him up. Now the only advantage of the Russian is his superior tie-break.

In the Open 16 category, Haik Martirosyan, as we already reported, only needs a draw to become a champion. The Russian Olexander Triapishko is just half a point behind, but the tie-break of the Armenian is much higher. As for the Open 14 category, the fate of the gold medals has already been decided.

source